(opens in new tab)

High Horse is a rotating opinion column in which GamesRadar editors and guest writers are invited to express their personal thoughts on games, the people who play them and the industry at large.

There’s a persistent argument constantly being thrown around in debates concerning the video game medium, and it’s one that I find particularly vexing. “Gaming is an adolescent medium,” they cry, “give it time to grow up!”

The argument is difficult to understand, and I suspect that it’s often used when a gamer finds themselves backed into a rhetorical corner by a non-believer. Rather than stick up for what games are and what makes them great, they shift the argument to say the true form of video gaming has yet to be realized. That like an adolescent child, gaming hasn’t yet figured out what kind of adult it will be.

Above: The Edison Kinetoscope was the start of film’s “arcade” phase

This is an outmoded saying, and it’s lost its use in the modern day. It may have been true in the dark days of the turn of the millennium, when babes and power fantasies still ruled the sales charts. However, gaming has demonstrated that its adolescent period is over.

Commercial games have been around for about 41 years. Our earliest experiments with commercial games, like Galaxy Game and Computer Space, started out much the same way film did with Edison Kinetoscopes. They were displayed in public spaces like fairs, colleges, and bars, and cost a small price for a small game/film. Since then, games have advanced rapidly.

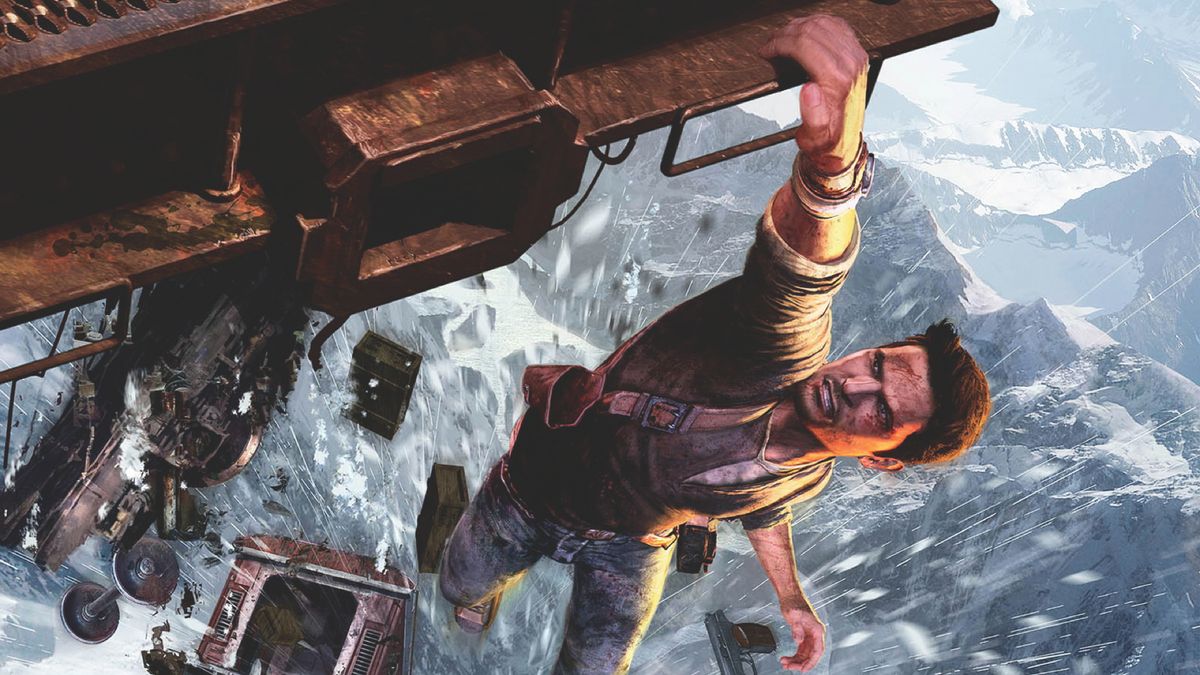

Since those early experiments, the fundamental form of video games has changed. From a starting point of basic dexterity challenges, games have found their footing as a form that excels with narrative (sometimes) and blockbuster excitement (often).

What baffles me is that many people seem to think that video games are on the cusp of a revolution. Were you asleep? I think you missed it. It happened in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Game developers started broadly experimenting with narrative in the ‘80s, and truly figured it out in the ‘90s with games like Final Fantasy VI and Metal Gear Solid, proving that gameplay can be an incredible force for serving narrative. Since then, narrative games have mostly been refining that formula. We also underwent a much quieter revolution in the 2000s, when games like Far Cry 2 and Bioshock raised gameplay itself into narrative.

Above: Far Cry 2, like Bioshock, did its best to weave gameplay and story together seamlessly rather than interrupting one for the other

Comparisons between gaming and film are overused, and usually illogical. But indulge me for a moment, because in this case I think it’s useful for comparison. By the time film had reached its 41st birthday (using the first public appearance in 1894 as its date of birth), creatives had already produced some of the American Film Institute’s greatest films of all time, establishing the form of the medium in the process. In many ways, the following 77 years have been spent refining (or toying with) the formula of films like Battleship Potemkin, City Lights, and King Kong. (Not shot-for-shot, but the basic formula of visual storytelling.)

Wonderful additions like color, sound, and computer graphics have kept film relevant in the modern era, but none have fundamentally altered the structure of visual narrative. And none have changed what people enjoy in a movie. What I’m suggesting – brace yourself – is that games may already be what they’re destined to be, and that any further changes will be minor tweaks to an already well-established formula.

Ask yourself if you’re comfortable with gaming as a hobby and art form if the next hundred years of our history will essentially be more of the same. Slow evolution, with no more revolution. After less than 50 years, film had Casablanca and Citizen Kane on its resume. I’m not suggesting that the creative timelines of games and film will line up, I’m suggesting that industrious creative geniuses work quickly. It’s unlikely that all of the geniuses in gaming history have missed something fundamental to gaming over decades of arduous study that a Digipen graduate will discover in five years.

Above: Super Meat Boy was a reminder that sometimes, the simplest games are the best

New genres will doubtless be discovered, but they’ll be built upon the foundation of player engagement that already exists, which is the central core of gaming. We should consider the possibility that many of the greatest games that will ever be made are already behind us. And that our greatest visionaries (Miyamoto, Meier, Wright, Molyneux and Kojima spring to mind) have already done most of the heavy lifting in probing the potential of games.

Today we find games returning to their roots, and the popularity of the medium has exploded as a result. We’ve spent the last 30 years trying to make games more and more complex, but the truth is that simplicity has always been gaming’s most potent ally. Facebook, Flash games, Nintendo and iOS are testament to that. It’s important to always remember that the people who frequent sites like this one are gaming’s “artsy” crowd – the tiny two percent of enthusiasts who care about trying new things and pushing the envelope in bigger, flashier experiences. This is the avant-garde, but the enormous majority of gamers are satisfied with gaming as-is.

By a wide margin, the most popular games of the modern day are centered around the beauty and purity of play and competition. Which, I can’t help but note, is right where we started from in the arcades of the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Above: Computer Space was the first real attempt to commercialize video games (ironic, considering it was an adaptation of Spacewar!, the first real open-source video game)

I fibbed a little bit earlier in this article. While games aren’t poised for a revolution, they’ve just had one. But it’s a backward revolution. After decades of seeking to justify their existence by mimicking every other medium, a new generation of game designers has risen to prominence by going back to gaming’s roots. The focus has returned to finding fun in a set of basic rules. Don’t let Meat Boy touch the saws. Anything can be mined; stay alive; dark is dangerous. Shoot the other team. Birds can’t fly; gravity pulls down; kill the pigs.

Games were in their adolescence when they were hopelessly holding onto the leg of their older brother, film. They wore his clothes. They acted like him. They used all the cool words they heard him say, then tried to impress their friends with what they’d learned. They tried to emulate others, rather than focusing on themselves and what makes their form unique. Amusingly, they often even acted like teenagers, simultaneously angry that the mainstream media wouldn’t pay attention to them, and also begging said media to leave them alone.

In this sense, gaming’s adolescence has ended. We’ve grown out of our little-brother complex, the pimples are gone, and we’ve become comfortable in our own skin.

Game News Video Games Reviews & News

Game News Video Games Reviews & News